Interview: Jude Barber

Jude Barber is an architect and director at Collective Architecture, based in Glasgow. Originally established as Chris Stewart Architects in 1997 the decision was made in 2007 to give all employees an equal share in the company and for it to be governed by cooperative principles.

As part of our on-going research, we have been exploring the variety of governance models for delivering projects and companies. We are keen to get insights into the reality of developing and running a cooperative practice and understand the positive factors and challenges. Rob Morrison met with Jude at their offices in Glasgow on 1st April 2016.

RM: I’m really interested to hear what it’s like to run a co-operative practice – the governance, legals and finances – and how that manifests itself in the daily running of a business. Could you give me an overview from your perspective?

JB: Principles of creative freedom and expression are at the heart of our studio practice where individuals are encouraged to pursue their ideas and develop skills under the umbrella of our shared vision and values. For me there are different ways of thinking about cooperative working and I think they are at their truest and most honest when they relate to governance, finance and how money is shared – how people are paid, how people make decisions so they can control their environment, their work and their labour. For me it’s as simple as that. You can talk a lot about collective working and collaboration, and that’s all fine, but for me it’s not truly cooperative unless you actively and frankly address issues like pay conditions and equality. Your point about governance, legals and finance are the bedrock of a cooperative practice.

Sometimes lip service is paid to the idea of collaboration – just because you’re all getting on and sharing ideas. But in the end it comes down to key questions – who was paid? How were they paid? And who took the profits? Was it given to someone else? Was it reinvested? The one thing we are quite clear about is that our governance and financial model is – one member, one vote – equal ownership, regardless of age, gender, role or experience.

RM: Is everyone a director of the company?

JB: No. We’re not a workers’ cooperative in that sense because the company started originally as a sole trader (by Chris Stewart) then it moved into a limited company, with two salaried directors and one equity director. We then became Collective Architecture and Chris gifted all his shares equally to the Collective Architecture Employee Benefit Trust – so now everyone who’s a Trustee is a share holder and equally owner of the business. In my mind, Collective Architecture is as co-operative as a limited company can be – we adhere to cooperative principles.

RM: So there is the limited company which is the legal entity, and the Trust is tied to that company?

JB: Yes – we have 3 directors registered with companies house, myself, Chris and Gerry [Duffy] and we still have our normal directorial legal duties but it is the Collective Architecture Trust – and all Trustees – that ensure we are employee owned, governed and controlled. For example, I could be voted out of my role by Trustees. So we all have the power to make decisions. People aren’t afraid to talk about those sorts of things, which is good.

RM: So the Trust has ownership of the company?

JB: Yes, which is a bit unusual because we’ve got over 30 Trustees and they all have a vote. At the end of the day, you’re still getting on with your work and running a business but it goes back to [the governance] being the bedrock. Most people work within a pyramid, capitalist model which doesn’t encourage people to have a voice and control over their own labour, finance and governance. That is currently the easiest way to set up a business, and most people have worked in that system.

RM: Have you found that people are more engaged with discussions around governance, do you find it increases people’s commitment to their work?

JB: Well its their work, its their business, its not that there is a sort of ‘otherness’ to what people do. On a day-to-day we probably don’t think about it too much. We are primarily working to create the best buildings and places that we can with our clients and collaborators. At one stage we became almost obsessed with the company structure and, as we go forward, we are starting to accept it as normal. For a lot of people working within a pyramid structure there is an obsession about their position in that structure, or how to move beyond a certain glass ceiling, and not having any control of what work you’re doing. So actually I think most people are actually obsessed with ‘it’, but perhaps in different ways. This is the first place I’ve ever worked where there isn’t some anxiety about pay and conditions. Everybody has issues, we all struggle with different things, but the difference is that there are no secrets, everyone knows what everyone else gets paid, everyone agrees to what everyone gets paid. There is total transparency. All the directors salaries are open. There are no secret funds. There is no disparity between people of different genders or backgrounds. There is a pay scale, which we all agreed to and talk about.

RM: What is the mechanism in place to have these discussions?

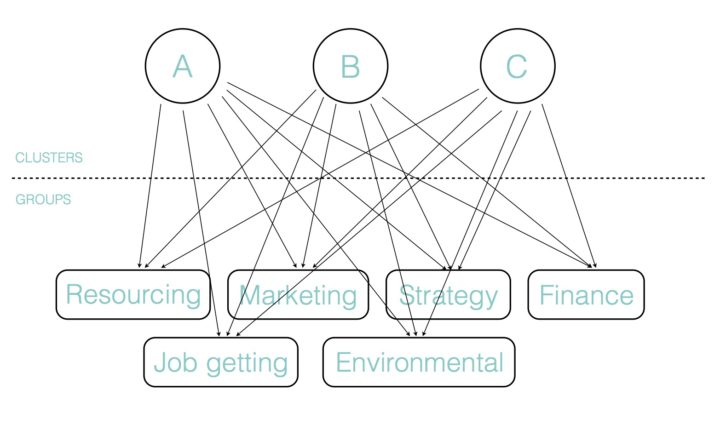

JB: We have an AGM [annual general meeting] every year, which is where we deal with the big stuff, which is where we assess our financial position, agree salaries, welcome new Trustees and suchlike. At this meeting we also look back on the projects we have created together and plan/strategise together for the next few years ahead. On a day to day, we have different groups within the studio; for example we have a group that deals with Finance, we have a group that deals with Job-getting, we have a group that deals with PR. Two years ago we started a group that deals with Strategy which looks at roles/responsibilities, succession-planning and our broader plans for the future. We work in small teams – or clusters – to share skills, projects and carry out internal design reviews.

RM: These roles are delivered by people within the company, not people being bought in to do specific jobs?

JB: Yep – these are architects, technologists, administrators, architectural assistants – which puts a bit of pressure on people as well because you’re doing your day-to-day job as an architect, but you’re also dealing with the management and strategy of the company.

RM: Do you think this increases a sense of accountability for the success of the projects and the company?

JB: Yes. You hope it plays to people’s strengths – some people are really good with finance – and it comes naturally to them. Others are really good at PR and promoting the company. So each group has people with different skills and most groups have a director associated to them. We then have our clusters which focus on projects, skills and quality.

RM: So how many clusters are there?

JB: Four – three in Glasgow and one in Edinburgh. We are getting bigger, so thats why we’re having to form clusters. When there was 15 of us it was easier to communication together, but now there’s 40 of us. Once you get over 15 people it’s hard to know what everybody is doing and meaningfully share ideas, so to break it down into smaller groups with greater autonomy and communication felt logical.

RM: I think that is an interesting aspect of a lot of creative organisations, especially in Scotland, where there is often very few opportunities for taking senior roles within organisations or companies. It seems that these hierarchical, pyramid, structures are often effective at dampening creative activity, rather than empowering it.

JB: Yes, I think its a complete myth that the creative sector is more fluid and leftist in its thinking in terms of organisation. Actually it often reverts to very traditional forms of class, hierarchy, patriarchy and all these things that are completely contradictory to how an organisation might be publicly represented and how they speak or express themselves.

RM: That’s a big reason why we are doing this research via Agile City, to consider governance structures that empower the creative process as oppose to hinder it by being burdened by bureaucracy. Does your work ever extend into working with clients to help them consider the design of the organisation structures as well as their physical environments?

JB: We’ve talked to quite a few people about what we do – some engineers, some architects. The good thing now is that there is Cooperative Development Scotland – who are just brilliant – they’ve got funding, case studies, advisors. We are constantly promoting this way of working. We have also recently become members of Employee Ownership UK. I don’t understand why people wouldn’t share their work and share their money more equitably.

RM: Perhaps its fear? Being worried about stepping into an unknown that will take a lot of time and discussion to resolve. If you were to look back on the last 10 years since becoming a cooperative, is there anything specific that you would have done differently?

JB: What we should have done is talk about our evolving roles sooner. But when we were about to start these discussions there was a massive recession and made a decision that [the company] keeping alive was more important than making changes. So we should have probably made some changes sooner but from a business point of view it was the right thing to do. We grew really quickly at the start – started at 15 – and grew quite rapidly to 25, and now we are 40. We’re now getting more responsive and nimble – less concerned about change.

RM: I read in an article about Collective Architecture that there isn’t a ‘house style’ – is this a result of your governance structure? Do you have a range of experiences within the design clusters and then keep the directors mobile?

JB: Yes. However, as we continue to work closely together we have noticed recurring themes and approaches developing, which is interesting. There’s a developing rigour and conversation about form and making. We’ve tried to group the project types together loosely, so its not as clear cut as a ‘housing’ cluster, so there is still flexibility because everyone most people enjoy working on a variety of scales and projects types. So the clusters are roughly grouped to share complimentary skills, interests and experience. Sometimes you’ll work together in a team of three, sometime on your own – but its always important that someone else knows the project you’re working on. Thats what we’re working on at the moment -to encourage creative thinking in a supported way.

RM: Are people within the clusters responsible for seeking new work?

JB: Absolutely. Most Much of our work is repeat work, so everyone is responsible for getting work and has the agency to seek and develop projects that interests them. And they all have direct relationships with specific clients. Our work is about building relationships with people and everyone is involved with that.

RM: And that supports the idea that everyone has a responsibility for the finances of the company…

JB: Yes. If there is no work there is nothing to do. We have always initiated projects – some of Chris’ earliest projects were self-initiated – like guerrilla lighting that became a community event, which became a proposal for funding, which then became a building. So there is a real understanding in our minds that you need to generate projects. We meet a lot of people through our various projects and that allows us to build up new relationships, instead of relying on networking or marketing activities. For us its about building relationships based on trust and being good at what you do.

RM: You’re saying that you’re growing and getting top heavy – what does your recruitment process look like? Do you have a HR group?

JB: Yes, we are all growing old together! This is great for experience and shared knowledge but it does raise issues about getting ‘top heavy’. Fortunately, our Strategy group is working with everyone to see how we can positively address and harness this in line with our ethos. We also enjoy working with younger colleagues and trainees. We’ve also always had people teaching, which allows you to sense people who work in a collaborative way, who can work in teams, are talented in their own right but can also listen. So we tend to find that a lot of our recruitment is through knowing student’s work and what interests them. We’re recently starting working with an HR consultant and this has been really helpful and positive.

RM: In the instance that someone isn’t working with the practice, do you have a mechanism in place that would allow that to be addressed?

JB: It doesn’t really come up to be honest. However, we all have our moments and sometimes you are more engaged and active in your work than at other times. So, you’ve got to think of your career as a long game. Everyone has strengths, and we all have the responsibility to ensure that we are working to those strengths and building on our weaknesses. Its also important to support people who have interests out with the practice so they are fulfilled on a number of levels. During the recession we did a whole redundancy chat together, which wasn’t a secret and we talked about what we were going to do. In the end we all took pay cuts for a few months and got over the hill. I think if you have responsibility for your work, an understanding of all aspects of the business, control over what’s going on and can affect change – then you’re more likely to focus on the creative aspects of your work and flourish.

Governance diagram of Collective Architecture: